Title (as given to the record by the creator): FaT GiRL Roundtable: Class/Conscious

Date(s) of creation: October 1995

Creator / author / publisher: Fat Girl

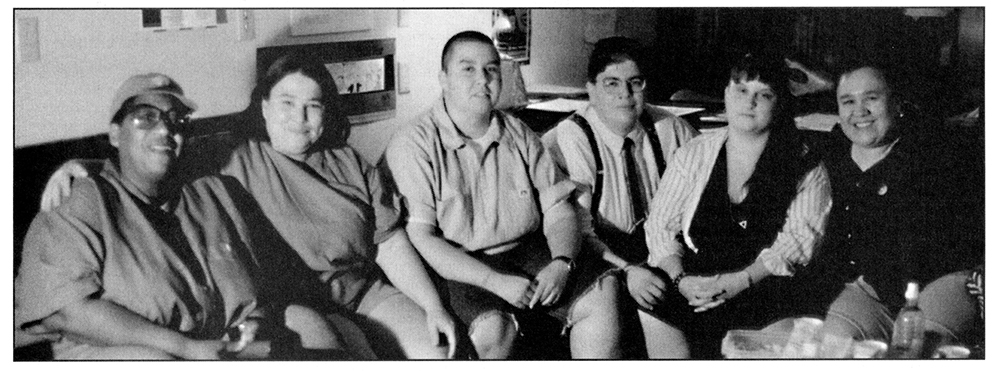

Physical description: Five zine pages of transcribed conversation and black and white photos.

Reference #: FG4-044-048-Roundtable

Links: [ PDF ]

CLASS/CONSCIOUS

Transcribed by Cath Thompson, Edited by Barbarism

The following roundtable is an excerpt from a discussion on the dynamics of fat and class between fat dykes (in order), Margaret Sloane Hunter, Hannah, Oso, Margo Mercedes Rivera, Selena and Lea Arellano.

Lea: My name is Lea. I’m Chicana. I come from working-class background, and I consider myself working class presently.

Hannah: I’m Hannah, and I come from a mixed-class background. My father had a white collar job most of my life, but my mother and my father grew up poor. My mother grew up really poor. She grew up in the back woods, with no plumbing and all of that. Both of my parents had jobs when I was growing up. Culturally, I identify with my mother, and I identify as working class. I’d like to make it clear that while my father was white collar, he never went to college. Because he was a white man and it was the fifties and he was lucky, he happened on this chain of events that led him into that world. And he died of a heart attack when he was 51, which—I think—talks about his class life at work. Right now, I own a business, which I think makes me middle class. The basis of my class analysis is somewhat Marxist. So, in terms of my relationship to the means of production, I own it.

Margo: My name is Margo. I’m mixed-race Ashkenazi Jewish and Latina. My father was raised poverty class in Peru. My mother was from a lower-class background. I grew up working class and have earned my living at working-class jobs for most of my life. I presently have a white-collar job but feel that I still retain working-class values.

Margaret: My name is Margaret and my parents are working class. I’ve been pretty solidly working-class background. I resist the word “class”; I like “income.” I’ve been around people who have a high income and don’t have any class. But I have a middle-income job; I work for the state, but I don’t own it. And I would very much like to be in a higher-class bracket than I’m in, because I don’t like struggling. I live from check to check, and so I guess that makes me pretentious. My parents are both black, African-American. When I was a kid, my mother used to put labels on hair grease jars for money, and then she went to night school. And then she got a job with the county. My father sold this little nickel-and-dime life insurance for a while. Then he worked at the post office, I believe, before they split up. My father then moved into a middle-class life because he bought a house, after many years.

Oso: My name’s Oso, and I’m a Chicano. I’m bi-racial. I was raised working class by my grandparents and, when they died, I sort of moved around from family member to family member, and took care of myself pretty young. And I recently married into money. My wife has … she comes from money, and her family is upper middle class, at least. So, I think right now I’m in a transition. I work at a bookstore—at Old Wives’ Tales. I don’t make a lot of money, but I am recently in a very privileged position financially.

Selena: My name’s Selena, and I grew up on welfare, with a single mother who was herself from upper middle-class, waspy background. She was a runaway as a teenager. I didn’t meet my father until I was 16. I’m not real clear on anything about that side of the family, except for I’ve met people, but I don’t know anything else particularly. My mom was struggling on welfare, and was working in job program to job program for awhile, until I got older. She went back to school, and was a school teacher. I was a student. One of the things that’s crucial to me, and it’s been an issue in my life about this, is the difference, the line, between how much money you have and the social class that you’re assigned, because there’s privileges you get from cultural mannerisms and belonging, and then there’s money.

Hannah: Something of interest to me is culture and class. My mother’s people are hillbillies. I did go to college, and I met a number of white, urban, working-class women who took a lot of my cultural mannerisms as middle-class traits because I was taught to be quiet and polite, I was pretty much written off as a suburban, middle-class white person. When I met Lea, it was a real relief to me, cause I don’t know any other hillbillies … That’s not true—I know one. It’s like we come from a similar culture. Poverty is a big piece of that culture because the values come from the poverty. I wondered if people wanted to talk about that—their culture and class, and how they interact. One thing about fat and class that’s really clear to me: in my family, the men are tall and thin, and the women are short and fat. There’s this big myth about how people get fat from eating a lot, and my mother’s mother did not eat a lot. There was not a lot of food to be eaten, and she ate the same thing as her husband, who was very tall and very thin. What her body did with it and what his body did with it were really different. That concept of fat connected with overconsumption seems not real to me. I read somewhere that in this country, as men get more money, they’re likelier to be heavier, and women who have less money are likelier to be fatter. That is how it is—the men are thin and the women are fat, and no one has money in my mother’s family.

Lea: I do notice that the thinner you are, there are a lot of assumptions about the more class you might have. I’ve seen that thinness is a more important value to middle-class and upper-class women. Not that it wasn’t something that was talked about in my family. The majority of people in my family are fat—not all of them, but the majority. But that wasn’t a focus; the focus was survival, and the focus was making sure that everybody ate, that everybody was fed. For me it gets a little bit convoluted because also, as a woman of color, there’s that whole piece about assimilation. They put a doll in front of you as a child, and that doll would be blonde and she would be thin, and she would be tall, and these were the images you were playing with as a kid. And I remember, as a kid, thinking … first of all, I didn’t like dolls, and I’m sure that there’s other reasons why I didn’t like dolls, but I remember one of the reasons I didn’t like dolls was because none of them looked like me. How my mother would deal with it, I remember corning home from school at about eight years old when she put me on my first diet, because I’d come home crying, and it was the kids would say, “Dirty fat Mexican. Fat Mexican, dirty Mexican.” And she says, “Well, you know what, we can’t do nothing about the Mexican part, but we can do something about the fat.” Because my mother believed diets worked.

Margaret: Were you in an all white … ?

Lea: I was in a white, working-class neighborhood, and there was only four children of color in my whole school, and they didn’t live in my neighborhood. Our family was the only family of color. So it was like she thought if she could help me lose weight, she’d be protecting and supporting me. I don’t think she would have done it if I wasn’t coming home a lot and complaining. What was important to her was that I was going to school, and showed up for school. That was what was important to her.

Margaret: I have a different experience. There’s the reality and there’s the myth. The reality is that a lot of successful black women were fat—mostly singers and entertainers, and stuff like that. Those were role models; those were people we applaud and clapped and everything, but I don’t know of any of my friends who weren’t berated by their mothers, particularly about weight, which is a big thing in my family. It doesn’t matter if in the family all the women are fat. It still was a big deal. I have to say not all of the women in my family are fat; some of them are quite thin. But that’s an issue. It’s a big issue—it’s always talked about. I don’t know if it’s so much embarrassment as that “we want you to be as successful as you can, and your being fat might hold you back.” You might not get the right boys, the best boyfriend. You might not get the best job. But in black humor there’s a lot about laying up with a big-butt woman and loving it. I’m talking heterosexual, now. There’s a lot of acceptance among black men of big titties, big butt, big-hipped black women. That’s just kind of like the thing. Yet, there’s still this thing about losing weight or being too big. On some levels, especially in this country, class can change by who you marry, or what job you get, or your income or whatever it is. I wonder if those things aren’t pretty universal. I wonder if the pressure for women to look a certain way is not something that crosses class lines. Because I hear middle-class women say the same thing—a different theme, a different reason, but still, it’s about women being put in a mold for whatever reason. But we can only talk about our own experiences, and our experiences are from the class background that we come from. My father died a couple of weeks ago. I went home for the first time in 20 years. I’d stayed away because I didn’t want to deal with all the fat stuff. It was just very interesting being back home, and I guess after being away 20 years, people knew; they didn’t say one word. I was much bigger when I arrived two weeks ago than I was when I left. But yet, there was still talking about other people, or when watching TV, having people comment.

Margo: My experience of being fat within my cultures has been mixed. My Jewish mother enjoyed her fat body and often would belly dance half-naked in the living room. My father also thought my zaftig mother was sexy. But from the outside world my mother got the message that it was not o.k. to be fat, so she intermittently made us both diet. Both sides of the family liked how I looked when I was just a little bit fat (around 200#). They’d say, “Oh, you look so healthy,” and they’d pinch my ass. But once I reached 250# and started hitting 300#, it wasn’t o.k. any more. The same grandfather who adored me five years before would incessantly badger me about how much I weighed.

Hannah: I don’t also mean to imply that it was acceptable for women to be fat in my family. I was not fat as a child, but I was told that I talked too much, I ate too much, and I was lazy. And one of my friends said to me, “Well, this is what I think you should do: you should talk more, eat more and work less. Those should be your goals in life.”

I think that is related to class, because I don’t talk a lot. I mean, I have always worked really hard, and I work really hard. That’s part of my cultural training, too. If you’re a woman, man, you work!

Lea: Culturally, that being an Indian, the closer we are to our indigenous roots, the less we worry about being fat. Because some of the Indian women that I come from are fat. They’re large, fat women. One of my favorite artists is Zuniga, and all of the women that he depicts are these huge women. And these are my ancestors, you know. My eight-year-old goddaughter Anivela, who’s my niece, is going back to school now, and she told my mother last week, “I want to go on a diet, because I have to go back to school on the 17th.” So in the summer, she’s cool. She’s going to her synchronized swimming, she’s going to her kung fu, she dances at the pow wows with other Indians. But here comes school, where there’s a lot of peer pressure. It’s a mixed school, so there are white kids and there are brown kids, and she doesn’t feel it in the summer. The activities she’s doing and the people she’s having contact with in the summer, and other kids that are in those activities, they’re not putting the pressure on her. One was synchronized swimming, where the bodies are very diverse, and it was 200 little girls doing synchronized swimming, and the only thing when I asked her what kind of experience was that, well she said, “The only complaint I had was that they didn’t choose me to be the one they lifted up.” So she says, “I really wanted to know what that felt like, to be lifted out of the water. My suit was sparkling.” I have a lot of transference with her, ’cause she’s going through exactly what I went through as a kid.

Selena: I know a little girl whose mother is also fat, and who is chunky. I don’t know if I’d call her fat. She’s a little girl, she’s big, muscular. Her mom is totally behind her, totally trying to counteract all the messages, but the girl wouldn’t ever say, ”I’m going to tell my mom on you.” She’d be like, “I don’t want to tell my mom. She’d make a big deal about it. She’ll go down and yell.” I don’t know why the difference is like that. It’s really hard to watch her still have the support and still go through all that pain.

Oso: When I was very young, it was okay for me to be fat. My family was mostly fat, and it was all fine until—and I think this was true for everything about me—until I hit, like, 12. And then I was supposed to stop playing with trucks, and stop playing with boys, and start wearing clothes that are like girl clothes. Therefore, to start being thin. And my mother didn’t care that I was fat, but people pressured her. When it was other people coming from the outside saying, “Maybe you should start making her wear dresses now. Maybe you need to stop buying boy clothes. Maybe you should put her on a diet.” It’s interesting, the kind of pressure that different people get. That isn’t necessarily from inside my family. A lot was from the outside, or from my aunts, who had left and got their own set of values about needing to lose weight, and then wanting to bring them back home.

Hannah: I think that a person has to cut a swath for herself. I would say that I’ve never been hard up for a date. I don’t go to places where there are little skinny girls looking for little skinny girls, because I don’t need that. I can get that anywhere. I really do feel, as part of owning my ancestors, I’m wearing my grandmothers’ bodies. I did not have their lives, and in a lot of ways, I am the freaks’ freak of my family, but there are things about me that are true to the integrity of who my grandmothers were. And this is part of it. You are looking at it. It’s not just being fat and working class, but it’s the whole package of it.

I grew up with my father who was a chemical engineer. I’m the first person in any generation of my family ever to go to college. And I got to college and totally freaked out because I did not belong there. Logically, I should have been able to just go right through college, go to law school or whatever, and to mutate into a middle-class person. But because of the totality of who I am, and a lot of other things, I just couldn’t make that transition.

Margaret: It’s interesting you say you feel like you’re wearing your ancestors. I’m not sure that my ancestors sat around eating Cheetos. I think my ancestors ate natural food, and somehow or other I got away from that. Culturally, the food I eat, a lot of it was leftovers and so it wasn’t the healthiest. What I’ve been struggling with in the last couple of years is how to appreciate what was good about my culture, and what is good about my culture, and get away from the public relations about my culture. Unromanticize stuff that’s maybe leading me to my grave. I think that there’s certain things that I’m struggling with not embracing anymore, and saying whenever we have a gathering, it bothers me that there’s so much food. I’ve gone through that back and forth over “is that self-hatred, ’cause skinny women get together?” —I don’t really care about the skinny women. I don’t care what they have at their table. I wonder, is it we’re trying to show, “Fuck! We’re fat! We can eat fucking Cheetos!! Fuck you!!”? Or, “fuck, I can eat a Cheeto and” [gags]. I struggle with that all the time, because I want to be honest about my feelings about my fat. I almost don’t have any reactions anymore about if the little kid on the street says, “Fat lady!” I like myself. If I want to go work out in a gym, or if I choose not co eat anything at this table, I don’t want to feel like I’m selling out the fat community like I have been made to feel in the past, when it was just terrible to talk about black women and feminism. That’s what I’m trying to struggle around this fat and class. And yes, I have this image of big, tender black ladies with big titties comforting and nurturing. But, fuck, we nurtured so fucking much, everybody’s sucked our tits away! Know what I’m saying? So I’m wondering how much of that is romantic? How much of that is really African? How much is it really healthy and good? And I don’t have answers for it. I know it’s something that me and some other black women have been talking about a lot lately. I’m 48 now, and the last some years now, I’ve really tried real hard to stop living my life for my daughter, for a lover, for the lesbian community, which I love dearly. Just trying to get to a place where, okay, this is me. I hope you like it, but if you don’t, I like it. And it’s a hard thing.

Lea: When I was little, I remember going hungry. And I know hunger is one of the worst pains I have felt. And I’m not necessarily talking about dieting or self-starvation. I’m talking about when there’s nothing! As a child, you’re really afraid, and you start hiding little cans of green beans and shit under the bed. After the first time I experienced that, I did that. I had this stash of canned food under the bed, and I don’t remember ever pulling it out and eating it, but I just had it there.

Margo: Does this ever go away? That’s the difference between poverty class and working class. I remember someone told me about Richard Wright, and how he grew up poverty class, and he never got over that. He was a famous writer, and he’d go around with little balls of bread in his pocket.

Lea: I think it’s always with you. I don’t think you ever totally get over it. I think it manifests in different ways. Since I’ve become adult, I’ve never gone hungry, except when I dieted or self-starved. And I think it is all connected.

Oso: Sometimes I get really weird about it. We just had this big elaborate wedding. Her family helped us with a lot of money. I remember standing there having this photographer take my photo and I thought even in this $300 tuxedo, hand-made for me, I still don’t look like them. There’s a picture we have of me with her family, and I’m just as dressed up and more than all of them. There is that feeling of not fitting, no matter what clothes I wear. Or if I try and make sure I’m saying all the right things, I still feel like it’s not my place. They could be just in shorts or whatever, and I could be completely dressed up, I still feel like you could tell. I feel like I don’t look like I’m from that space.

Selena: I feel like that everywhere—not everywhere, ’cause I’m from Berkeley. Berkeley people are weird; sometimes people are weird. But I don’t fit in, really, with the sort of normal suburban middle class, that I wasn’t raised with it. But I don’t fit in with a lot of working class cultures, either. I’m culturally different. Especially, when I was in college, where people tend to be a little bit more self-righteous and see everything in two shades.

Lea: You know, this is working class stuff. There’s not a moment that I don’t think about money—when I go out to eat and what I order. I’m going to tell you, most of the time, what I order is determined by what I have in my pocket. It’s not determined by what I want. It’s very seldom that I go to a restaurant and order what I want. That’s where my income is right now. And even if it wasn’t, I think that I’d still do that, because I have all of those things in my mind. My last girlfriend took me out to dinner (for my birthday) at this incredible restaurant—and she spent $65, and I said to her, “A family could have eaten on this for a week.” I’m sorry. I didn’t want to sound ungrateful or anything, but that’s what I thought about when I was eating.

Oso: I had a lot of anger about coming into a relationship with someone who I felt had all this

privilege all her life. I feel she worries about money, and I’m, “You don’t have to worry about money. What are you worrying about?” I think that I had to fight getting into always being like, “Well, we should just go out. Or we should just pay for this person, or whatever, because you have it. Why shouldn’t we … ” I felt like I didn’t have it, and now you have it, so let’s use it. So it’s been an interesting struggle for me to realize how to balance it.

Lea: In my family, the females have a big loyalty about money and each other. Not about the boys—the boys are doing a lot better than the girls. But it’s like that. It’s like whenever we have some money come into our life, even if it’s not a lot, what’s the first thing that happens? We share it. I’ll send my mother this much; I’ll send my sister this much. And they do the same thing to me. But we don’t send the boys shit—they don’t need it. And they don’t send it to us, really, unless we ask. That’s just a female loyalty we have around money and class with each other.

Hannah: I really believe that people who have privilege can’t see it, or can’t see much of it. I know a lot about class, because I basically identify as working class. I can see it all around me. I’m white and I feel very ignorant about race, and I’ve worked very hard to deal with racial issues in my life, so I can not hurt women of color who I love. Like Lea’s mom is like my mother, and so when people say stuff about Chicanas, believe me, I take that personally, because it’s that way. I’m married to someone who’s middle class, and I see the class stuff in her family. The bottom line is that they just basically—not personally, but basically, in general—think that they’re better than me because I’m working class. They never say that, but it comes out in ways. I find it very hard to be in that type of relationship with a person from another class. If you can manage it, that’s great, but it’s very hard.

Margaret: Are they working class? There’s class-conscious people. I think that would make a difference—consciousness and how they use their privilege—used it or abused or not used it, or whatever it is.

Lea: I had that same thing happen with a middle-class, sort of on the borderline, upper middle-class Puerto Rican/African-American woman. Her family never took me seriously as her partner—never. When she started being with middle-class/upper middle-class other women of color, they took them seriously. But I never was up to snuff with them—ever—and I knew it, that I never would be. It was almost like they expected me to entertain them. That’s what I was good for.

Oso: My in-laws are good Berkeley liberals, so they have all the right rap, at least on the outside. And I think also they were so scared about me and the way I looked, that they had such a hard time getting past that to even let themselves get into racial issues or class issues. It took them months to get past that I didn’t have hair.

Selena: “Hey, that bald girl’s not white.”

Oso: They had this thing, “Oh, I like this person. She must not be all these things that I don’t understand. She must not be so different.” So they would ask, “So where did you go to college?” And I’d say, “I didn’t go to college.” “Oh, so do you have brothers or sisters, or anything?” Her father asked me about my family, and I was trying to tell him that I do have a half-brother. He said, “Oh, where does he live?” And I said, “Well, he’s in prison.” And he’s a little hard of hearing. “Uh … uh … oh, anyway, let’s have some cake.” I think they have a hard time seeing things that they think of as very different in someone they think is a nice person.

Lea: There’s a book that’s just come out—Lesbians Come Out of the Class Closet. I’ve been reading it and I’ve really been enjoying it. I really want to find more language to talk about this. The more I talk about it, the less of a sting it has. I think talking transforms it, can transform it. I don’t want to be punished for what class I come from, and I don’t want to punish anyone for what class they come from. I’m really not interested in that. I just want us to find a way to respect each other and communicate about it. Because I have friends, and I love them dearly, but still they say things, and it’s like, “Ouch!!” And you know what? I do it too. I may not do it about class, but maybe I do it about other things. And I want to hear the “ouch.” If somebody can’t say anything to me … if they say, “ouch,” I’ll know there’s something I need to learn. Because we get alienated, then we get isolated, and I think isolation is what’s killing us. I know that it’s one of the hardest things for me that I’ve felt isolated and alone. And I don’t want to. I want to be in community, like I used to be in the ’70s.

Margo: I agree with you, and I think most people don’t want to talk about class anymore. I think that people I talk to, they see class as this thing we talked about in the ’70s. I feel very relieved that I’m in a relationship with another woman from a lower class, but it also feels like we’re miles apart, because my parents did own a house. My dad was a cabinet maker. We worked every weekend at the flea market selling stuff to make money, and we did it on our own. It’s in a very working-class neighborhood, but it’s still a house. It still had a driveway. It still had a backyard. And my lover comes from poverty class, and she grew up in the projects. And that’s miles and miles apart. It would be miles away from somebody middle class, but it’s still a huge difference. I think it’s good you bring up this book, because I think it’s an issue that’s on the table again.

Selena: Something I’m glad to talk about, although I was dreading coming in here—not consciously dreading. My body was dreading it, just because there’s been so much pain in my life around it, and I haven’t sat down and talked about something like that since college. Somewhere after college, it was very judgmental. It was like everyone sits there and tries to say exactly the right PC line, and everyone else sees if they get it wrong. And that’s license to attack them. Talk about feeling “ouch,” I felt it from my mother. ‘Cause my mother is upper middle class, culturally. She’s got this mentality … she manages to maintain a lifestyle beyond mine on the same income. I don’t know how she does it. I’m convinced you’re just born with that and you just create it around you. I don’t know. I can’t do it. So there’s that division where I don’t feel like—there’s some very real ways in which I’m different. She’s always telling me, “Oh, just go ahead and buy it. Oh, it’s okay, put it on the credit card. It’ll be all right, it’ll be all right, it’ll be all right.” For her it is all right. I feel sick to my stomach over that kind of thing, ’cause my experience is, it’s not going to be all right. You don’t know where the next money’s coming from. And it’s really good for me to get to be in a relationship with someone whose class background is pretty similar to mine. I’ve been in relationships, the hardest one I ever was in was with a Chicana woman whose family had a lot more money than me, and they were working class. So it was like we crossed. I was poor but middle class culturally, and she had a lot of money. And my girlfriend now is from basically hippie-freak parents. You know, people that were poor, but were from another cultural background. And it takes a lot of pressure off. It wasn’t until I was with her that I realized all the tensions that there were either way, being with people that grew up middle class with money, or people that grew up working class with no money.

Lea: These labels, I’d like to examine them, because “working class” — what the hell is that supposed to mean? Because a lot of times, my father didn’t work. So I say “working” working class, but it came and went—the work. And that really affected us. And that when we had poverty was when he and my mother weren’t working. Except that my mother always worked in the home full-time, plus!

Margo: And you know what else?! I heard somebody once define what working class was—it just meant that you worked. But you could work at anything. If you were a doctor, you worked. If you were a lawyer, you worked. So therefore, you were working class, if you worked. And I don’t know where that comes from.

Hannah: That’s why I like having the basic frame reference that I have, whether it’s tired, useless or whatever. To me, there are some basic things that give me some clue, that just because your father was a doctor and he worked, that does not mean you’re working class.

Oso: Well, like everything, right? Like we all identify as fat dykes, but we’re all really different sizes. And working class to one person means like a really different amount of income to other people.

Lea: Even being able to work, these days, is a privilege, because there’s so much illness in society. So it’s really changing the face of class.

Got Something You Want To Talk About?

ORGANIZE A ROUND TABLE

Send a copy of the tape or transcription to:

FaTGiRL

XXXXX

San Francisco, CA 94114

FaT GiRL #4 Pages

- FaT GiRL #4 Cover

- Comic: Fat Dyke Action

- FaT GiRL #4 is…

- Letters

- Editorial (Happy Birthday!)

- The Sa/Me Debate

- Joanne

- You Are Cordially Invited to Join The Kitchen Slut for Dessert

- Wet Hibiscus

- Outrageous or Courageous?

- Southern Hospitality…and Northern Exposure

- You’re Crazy, Your Life’s Outta Control, & You Should Go To Weight Watchers

- Review: Martha Moody

- A Fat, Vulgar, Angry Slut

- Fat & Healthy

- Poetry: arms bigger than, first date

- Story: Arrival

- Potty Training

- Confessions of a Fat Sex Worker

- Laura Antoniou’s Some Women: a brief report of my favorite essay

- Comic: True Tales from Life in the Fat Lane, Part II: The Family

- The Fat Lady Emerges and Takes Aim

- Report from the Front

- Survey: What do you want from your non-fat allies?

- FaT GiRL Roundtable: Class/Conscious

- Bo & Chrystos

- Poetry: Goddess

- Poetry: Touch Mirror

- Advice: Ask the Gear Queen

- Stories: Washing Up

- Barbarism in the Cemetery

- Survey: What’s Sexy About Fat Women?

- Write On: the lip service update

- Fat Watch

- Photography: Lanetta

- Resources

- Cuntributors

- Personals

- Back Cover FaT GiRL #4