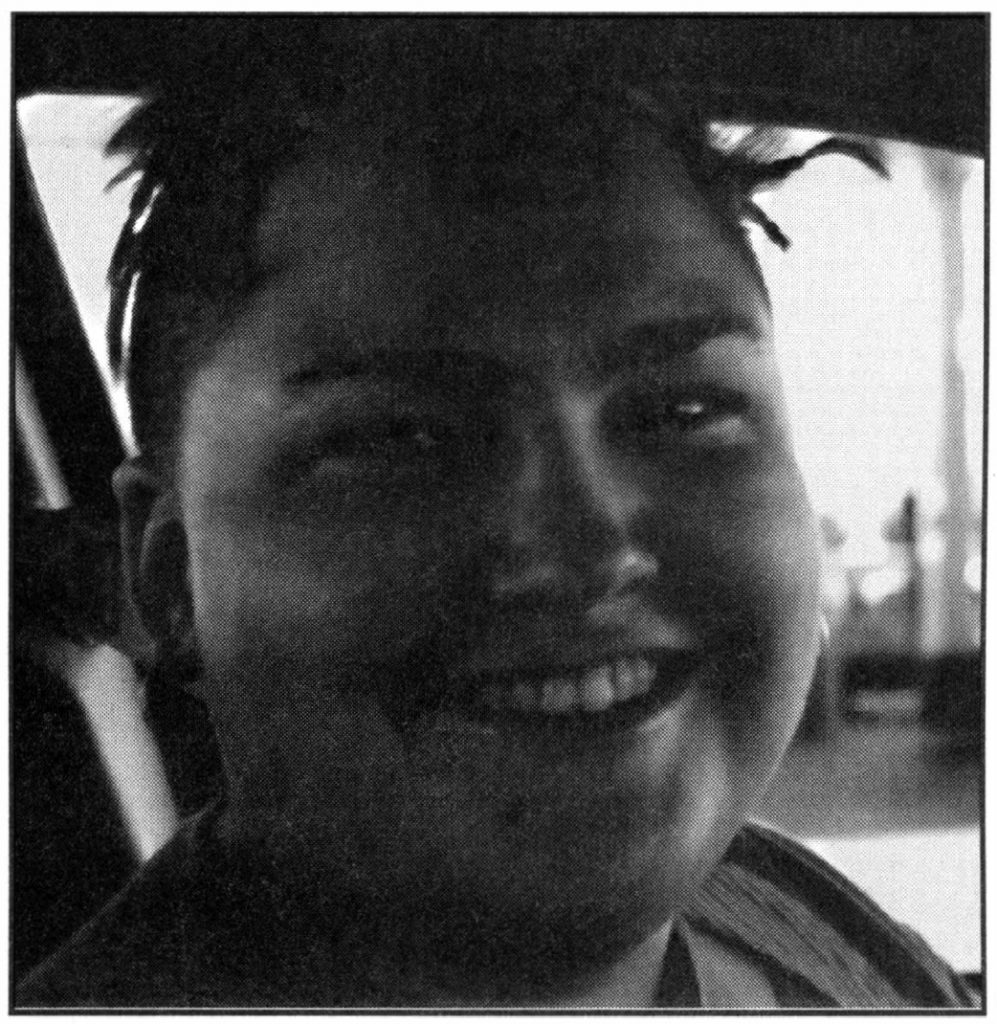

Title (as given to the record by the creator): Joanne

Date(s) of creation: Issue 4: October, 1995

Creator / author / publisher: FaT GiRL

Physical description: This two-page spread includes photographs, typed text, and clipart. Scan from a zine, black and white with purple ink.

Reference #: FG4-010-011-Joanne

Links: [ PDF ]

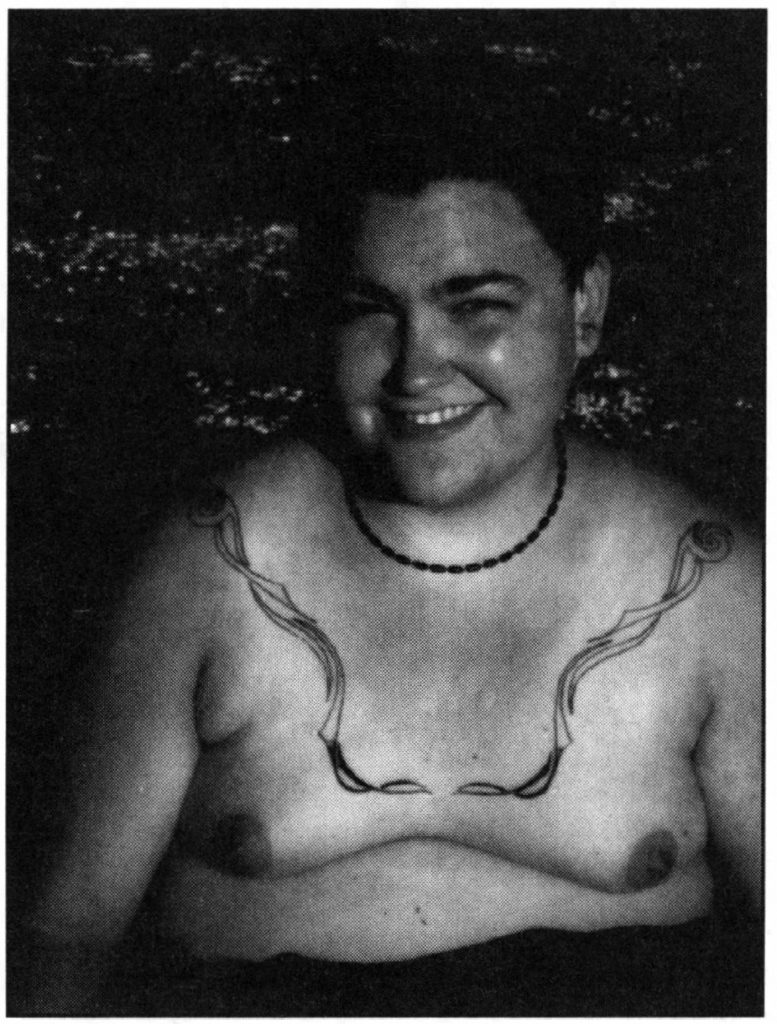

Joanne deMichele

December 21, 1973 – August 29, 1995

Contrary to common belief, Joanne didn’t overdose on heroin. She died detoxing. Joanne went to S.F. General Hospital and was refused compassionate withdrawal meds.

“Kicking’s a bitch,” she was told. Joanne waited in the lobby of General Hospital over twenty-four hours the week before she was actually admitted. Admitted with active TB, a bladder infection, a sprained ankle, dehydration, malnutrition, and heroin withdrawals. General was uncompassionate and rude towards her and her roommates, trying to get her out of there as soon as possible. She was in overnight, then released. Her vital signs weren’t intact. She couldn’t walk—not even with a cane or crutches—she was so weak. Her roommates carried her home, she laid on the couch and died that morning.

Joanne is dead due to General’s negligence and disregard to a fat, user, dyke, whore’s life. They killed her. If they had admitted their neglect she might have been able to get better care elsewhere. Instead, they pretended they were doing the best they could.

I went to General and talked to a head nurse interested in more humane and responsible care for the poor. Of Joanne’s story she said she’d heard a hundred of the same. “It’s all about health care reform. The medical field has become free enterprise and the care is getting shittier.” She said to vote (*whatever*) and to write letters to editors, which, although I’m pessimistic about, I encourage people to do. That’s Joanne’s story. I wish there was a way I could say this neglect will never happen again.

If you have any ideas or want more information, call BACORR (415) 437-4032.—Erica B.

You cruised me in the airport on the way back from the March on Washington. Sly smile, sparkling brown eyes, strong shoulders for days, and a cute defiant gait. You wanted to move from Seattle to San Francisco. Soon after, I was helping you and your mom move into our flat. Life couldn’t have been more thrilling. So much to choose from, you couldn’t make a decision.

A message scrawled on a scrap of paper amidst dirty dishes. Joanne died. Call.. ..

Things I will remember. Your endless questions always putting me on the spot and how you’d listen outside my bedroom door to me having sex with that sly smile on your face. Watching you watch all the girls. Swapping fat girl clothes and stories. Dressing up as horny housewives and playing truth or dare. Your way with words and the poems and endless letters you could write and I could never answer. How you hated your friends for being junkies and not listening. How cool it all seemed. All the beads you’d weave into strands of dancing color as vibrant as your laughter. Anger and missing you.

All the conversations you never finished. You choosing to survive and kick. No one listening. And then you’re gone. Dead at 22? Fucking drugs and no money and no health care and if you’re a fat working class sex worker dyke addict pervert nobody gives a flying fuck cause they are so afraid of being like you they can’t take the time to know you. —Barbarism

I almost didn’t recognize her, the last time I saw JoAnne. I saw her from the back and recognized her shaggy purple hair, but the person standing on the corner of 16th and Mission was so much skinnier than she was. But then I hadn’t seen her in a couple of months.

She turned her head—it was her. I yelled after her, “JoAnne!”

She came toward me and we chit-chatted. She was on her way to get supplies for a party she and her roommates were having that evening; I should come. But I had other plans.

How are you doing? I asked in that tone of voice that meant, have you kicked yet? Of course she hadn’t. I knew it from how thin she was—at least 60 pounds lighter than when we lived together—and how gaunt and gray her face was. Her eyes flicked about in that evasive way learned from being high.

Everyone keeps telling me how good I look that I’ve lost so much weight, she said almost bitterly, even people who know. I didn’t know what to say; she didn’t look good, but I could see how people whose measure of attractiveness was weight might think so, if they could ignore the gray skin and nervous eyes.

You should come by on your way home, I told her—I still have those books for you. I’d promised her some books that made a difference to me when I kicked: Ram Dass’ Grist for the Mill, Aleister Crowley’s nineteenth-century tale of kicking cocaine, and an inspiring biography, Assata. Yeah, maybe I’ll be by later she said. We hugged, a genuine hug, and each went our own way.

We shared vicarious lives, JoAnne and I. When she first moved to the City and was anxious for its realness, I told her tales of my life as a junkie in L.A. years ago. We sat on the back porch, smoking, and I shared my romantic view of heroin-the view few others were willing to admit, I thought. I was glad to have an audience that didn’t share the judgmental attitude of most people. I told her how being high was like Sunday morning, everything was fine and you just didn’t care. I told her how pathetic I became, letting slimy junk dealers feel me up so I could cop. I told her

how sticking a needle in my arm was euphoric and uuunph like sex, penetration and all. I told her how I’d throw up, every single time: a quick nausea would build in my stomach a few minutes after shooting up and I’d go vomit neatly into the toilet, then relax into my high. I told how at one point, when I was still able to make that decision, that I’d considered stopping junk, but didn’t because for the first time in my life I was losing weight and feeling good about how I looked. She shared how she’d gotten addicted to speed at age 12 or 13 for similar reasons, taking the usual route through diet pills, but managed somehow to quit cold turkey. She thought maybe that was why at almost 20 years old she still hadn’t started her period.

I told how we’d use needles over and over again until the metal tips broke off because there was no needle exchange back then—and how careful we tried to be about bleaching them every time. I told how one time I almost OD’d—I actually turned blue but my friends revived me—because I’d had a glass of wine before junk. And how eventually I’d shoot almost anything—sleeping pills, whatever—just not to have to face wanting to die all the time, being disappointed every time I woke up to another day.

I told her how I’d been unable to live without it because I was suicidal—yet how in some ways it kept me alive, sedated me, and kept me from taking that final step. And how I’d been lucky, been able to beat the odds and quit, thanks to a cushy country club rehab center courtesy of my white middle-class safety net (great health insurance). And how I’d done it here and there since then without getting myself re-addicted. And how it wasn’t heroin, it was people’s ignorant attitudes about it that made it so socially stigmatizing and isolating.

I don’t know what this all meant to her, but when she started shooting up I felt both responsible and secretly giddy. When her roommates found out and kicked her out, I felt protective of her and indignant of their assumptions that shooting up would make you steal from your friends and flake on the rent-after all, I had never stolen from my friends! I became her sometime drug counselor, defended her to our friends and kept trying to ignore the idea that this might be a “safe” way for me to use occasionally.

When it was obvious that she couldn’t stop, I counseled her: move away from your junkie friends, go to meetings, try to get into a treatment program. I told her of my own experience playing with needles—at first I was afraid that doing S/M with sharp points would be a “trigger” for me, make me want to use; but after trying it, I found that it satisfied my needle lust, got me high in a much cleaner and purer way than junk, and safely channeled my self-destructive urges. Some naive part of me thought perhaps S/M could save JoAnne from addiction.

We did use together once; it was ugly. She had a hard time hitting a vein through her thick flesh so she poked again and again in frustration, leaving tiny spots of blood along her arm, before finally hitting. My big veins were easy, but I took too much and was nauseous and vomiting for several hours. That was the third or fourth time I’d had that experience at separate points in the past four years, and I realized that the only way heroin would ever be good for me again would be if I did it repeatedly—something I’m not willing to do, at least not until I win the lottery.

After that night, we met for lunch a couple of times and talked on the phone. Each time I shared my experience of getting clean with her and tried to give her real advice and help. At one lunch, she told me excitedly how she was making so many changes in her life to make it easier for her to quit: moving into a sober household of queer punks like herself, getting into therapy. Yeah, but when are you gonna quit? I asked. I know how hard it is, I told her, and anything that makes it easier is good, but you just gotta do it. I knew she wouldn’t quit until she was good and ready. She tried a few times, even moving home to Seattle for a month at one point.

After I saw her that last time at 16th and Mission, I wondered to myself: if she would’ve been okay with her body image, might that’ve enabled her to quit? Maybe, like me, she’d kept doing it because she was losing weight—until she lost the ability to choose. Yeah, it’s a lot more complex than that—but I remember being 19 and suicidal and feeling fat and ugly, and junk not only let me not care, but starved me skinny. Is it bulimia if you use heroin to throw up? —Anonymous

From assassin child, by Joanne deMichele

you will be the assassin child/ bringing water pistols filled with piss/ to theme parties in 1999.

we will be the Wild Children/ thinking in images/ hide and seeking./ we will be the Wild Children/ sharing superstition like penny candy/ pulling the pigtails of our demons,/ slitting our wrists to become blood sisters./ this world our school room,/ these city streets our playground./ we will be the Wild Children/ unwanted, unwilling to play certain games,/ swearing: cross my heart hope to die stick a needle in my eye!/ we will seek each other out for survival/ and find majic like bugs in each others greasy hair./ we will find majic in the darkened allies/ where the Wild Children are rumored to gather/ and scheme/ and spread.

you can be my terrorist/ and i will be your poet.I you will be unauthorized/ and i, undiscovered./ we will fill the walls of the president’s bathrooms with threats of freedom; poetic terrorism./ we will watch our backs,/ sharpen the knives on our tongues,/ carry each other home on hopes that things can change/ and expectations of assassination.

FaT GiRL #4 Pages

- FaT GiRL #4 Cover

- Comic: Fat Dyke Action

- FaT GiRL #4 is…

- Letters

- Editorial (Happy Birthday!)

- The Sa/Me Debate

- Joanne

- You Are Cordially Invited to Join The Kitchen Slut for Dessert

- Wet Hibiscus

- Outrageous or Courageous?

- Southern Hospitality…and Northern Exposure

- You’re Crazy, Your Life’s Outta Control, & You Should Go To Weight Watchers

- Review: Martha Moody

- A Fat, Vulgar, Angry Slut

- Fat & Healthy

- Poetry: arms bigger than, first date

- Story: Arrival

- Potty Training

- Confessions of a Fat Sex Worker

- Laura Antoniou’s Some Women: a brief report of my favorite essay

- Comic: True Tales from Life in the Fat Lane, Part II: The Family

- The Fat Lady Emerges and Takes Aim

- Report from the Front

- Survey: What do you want from your non-fat allies?

- FaT GiRL Roundtable: Class/Conscious

- Bo & Chrystos

- Poetry: Goddess

- Poetry: Touch Mirror

- Advice: Ask the Gear Queen

- Stories: Washing Up

- Barbarism in the Cemetery

- Survey: What’s Sexy About Fat Women?

- Write On: the lip service update

- Fat Watch

- Photography: Lanetta

- Resources

- Cuntributors

- Personals

- Back Cover FaT GiRL #4