Title (as given to the record by the creator): FAT GiRL Roundtable #2

Date(s) of creation: February, 1995

Creator / author / publisher: FaT GiRL

Physical description: Eight zine pages of transcribed discussion between several people, and photos of them.

Reference #: FG2-008-015-Roundtable

Links: [ PDF ]

FAT GiRL Roundtable #2

Fat Dykes from divergent cultural, class, and age perspectives getting together to hash out issues of Age and Fat? You got it!!!

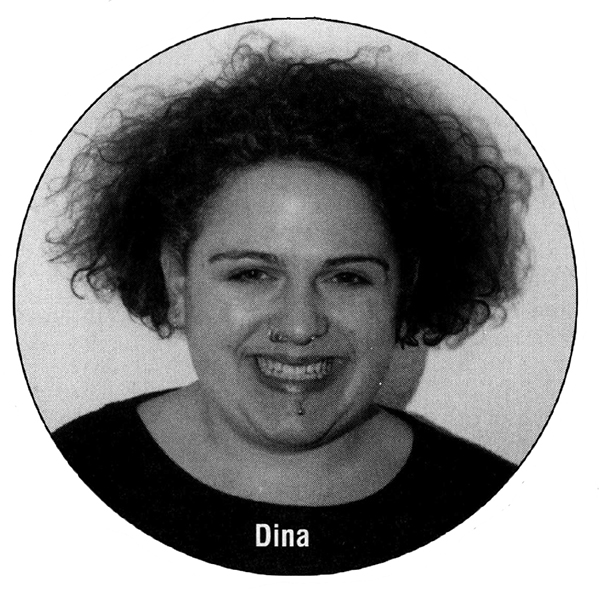

With: Judy Freespirit, Jasmine Marah, Lea Arellano, April Miller, Max Airborne, Dina Palivos

Facilitated by Barbarism

Photos by Laura Johnston

Barbarism: Can we start with introductions? Say who you are, and how and when you were politicized around issues of fat.

Judy: My name is Judy Freespirit. I’m 58. I was politicized in the early 1970s, right around the same time I came out. I was about 34. It was right at the time I was starting work on fat issues that I was in the process of coming out, so it was a very intense time all around.

Lea: My name is Lea Arellano. I’m 42, I’ll be 43 next month. Yay for aging! I also was politicized around fat in the late ’70s, and I was growing up somewhat isolated in Tucson, Arizona. And I was reading Plexus, that’s where I was getting information about the fat women’s/fat dykes’ political movement. And that’s actually one of the things that drew me to the Bay area.

April: I’m April Miller. I’m 31. I guess I was politicized about fat pretty much starting when I was in 9th grade. That for me was sort of like the chrysalis moment: when I was in the 9th grade and went into a medically supervised month-long diet, a 500-calorie diet in a hospital, and I lost all sorts of weight until the point when I started to plateau out and gain weight; my doctor turned into a total screaming raving maniac and turned on me and accused me of cheating on the diet because there’s no possible way I could’ve gained three pounds. I haven’t ever been a candidate, I mean I wouldn’t say that I immediately became wonder-political-person, but I never really bought it after that.

Dina: My name is Dina Palivos, and I’m 24. I guess on a really personal level I was always politicized around fat, because I come from a fat family, and there were a lot of issues with my mom. I was really close with her. [There were] a lot of control issues around her size, so I had a lot of ambiguous feelings around that, but for the most part that really crystallized all the really screwed-up ways fat people are treated. She was ill most of her life. She had all kinds of complicated illnesses, and of course “all of them had to do with the fact that she was fat.” No, they didn’t, but that’s what she told and was really punished for it. But on a personal level I became more political around it probably in the past year since I’ve moved here, because a lot of the stuff that happened back then had put me on the rabid diet … not wanting to end up having the pain that she had experienced. I brought that to a halt about a year and a half ago. I became more conscious about being happy with myself, and figured out why I shouldn’t necessarily starve myself.

Jasmine: I’m Jasmine Marah, and I’m 48 we just figured out. When I met Judy in ’75 was the first time that I became really politicized around fat issues. I was a different size than I am now, but still a fat woman, a smaller girl. And I’m continuously becoming politicized, but I never feel like I’m there, like I’ve got the picture.

Max: My name is Max, I’m 28. I would say I first became consciously politicized about being fat when I was 15, and I had been just released from a mental hospital where I was kept for being fat, and put on 500 calories a day, with constant threats, and stuff like that. But there was only a certain level to which I could really internalize being angry about being fat. I was still so self-hating at that stage that like, I could read Shadow On a Tightrope, but part of me just didn’t get it, and couldn’t hear it. I wasn’t ready. So, it has been, like you said, continuously evolving in my consciousness about fat. I’d say that I just am newly politicized about fat through doing Fat Girl. It has really made me think about fat and talk about fat on a daily, hourly basis, and put me in the public eye to everyone, fat and thin alike, as being someone who’s dealing with this issue who people can talk to about it. So every conversation I have practically, has to do with fat. I’m making myself talk about it now, way more than I ever have.

Wow, nice age range we have. If only we had a teenager and

Lea: -Someone in their 70s or 80s.

Barb: So, the first question to address is how do you feel your age and weight affect your self-perception as a sexual dyke? How do you think they affect others’ perceptions of you, and how has being fat affected your sexuality?

April: Loaded! Let’s start with the easy ones here!

[Laughter]

Lea: Well, as far as age and weight goes, I really feel like I’m in my prime. As far as sexuality goes I’m in my prime, I have enough hormones for all of you and then some.

Judy: I could use a few, thank you.

Lea: So, the hormones are really determining how I feel about myself sexually. I feel very alive and very vibrant, very passionate. My weight? You know, I have really good days and I have really bad days. Fortunately the good days outnumber the bad days. Most of the time I feel good about my body. Especially if I’m around fat women who are self-loving. But, things happen, and that internalized oppression comes up, the self-hatred comes out. But it doesn’t stop me sexually. How do they affect others’ assumptions of me? Well, there’s ageism, so it depends where people are on the scale of age how my age affects. But I’m still kind of in that “acceptable” age range, that’s how I feel. I’m still young enough, I’m not too old and I’m not too young, you know? I don’t feel oppressed as a 42-year-old person. And I’m not in those communities where I would be. So, as far as others’ perceptions about me sexually as a fat person, I know there are people that feel positive about that in me and there are people that are repulsed by it. My focus is on the people that feel positive about it, because I’ve worked my butt off to feel good sexually: because I’m a survivor, because I’m a woman, because I’m a dyke. I have worked my ass off; you’re looking at 17 years plus of therapy, not to mention all of the other things I’ve done to heal myself. And finally I’m enjoying my sexuality in ways that everyone should. Being fat affected my sexuality, like I said, it doesn’t stop me bottom line, but I do have moments when pain comes up around being fat, and I always wonder what my partners are thinking about my body. Sometimes I can ask them out loud. Sometimes I can have dialogue in a way that’s healthy and peaceful, and sometimes it’s not healthy and peaceful, sometimes it’s angry and raging. It’s there. It also depends on who my partner is, and how politicized she is and how evolved she is. And I have been involved with women who are very evolved around fat issues and women who haven’t. My last lover I really had to educate, she was not a fat woman but she was a 60-year old woman, and the aging and the fat stuff connect up in some very important places, so she was really educable.

April: I know that for me, for the first time in my life I’m starting to feel like my body, the size of my body, the apparent physical sexualness of my body, my age, my temperament, and my ability to be in control and be sexual in the world and accept that part of myself are all actually starting to get to the same place. I’m starting to feel kind of good about it. For a long time I had a body that was — from the way other people behaved about it or towards me — miles, ages, years older than I was. It’s finally getting to be something that’s closer.

Dina: I think initially my weight really affected my perception as a dyke. I came out and my weight increased really dramatically over a period of 6 months, and it changed my perception of myself as a sexual person, period, and then it also changed my perception of the type of dyke I should be. I didn’t know any dykes. I grew up in Detroit, and my best friend was a fag, and we came out together, and I didn’t know any dykes, I didn’t know any women, I didn’t know anyone, it was just the two of us. And the dykes that I did meet were very … it’s kind of like coming from being a really straight-identified girly punk girl to being a lesbian, and the world of what being a lesbian was so different than anything I’d known, and really, there weren’t a lot of things that were presented to me that were really my thing; musically it was really different. The politics are the one thing that I really got into and went with. But I just assumed because I was bigger and because I got to be bigger and I was really unhappy with my body and couldn’t really camouflage it, I kind of went with this butch thing, which is pretty laughable to a lot of people about me. I was all, (in femme voice) “no, I can be butch, I swear! I’m your daddy, really!” But it really had an impact on me, and I didn’t have a lover for a long time after I came out. When I did have a lover she was working this kind of butch action. That was not there, it was femme-on-femme action with butch-on-butch drag, and I couldn’t even pull off butch drag, so that really had an impact on me, my size determined how I felt like I should feel about my body, my sexuality. When I moved to Seattle after that, and had a lover, the way I would interact with her sexually was very much all about her and her body and I was extremely uncomfortable with any kind of contact with my sexuality. I realized I was really physically out of touch with my body, too. When I moved here, I started taking more control over myself and my sexuality. I was getting into what happens in this town and transforming. And I came out as femme, and I had a butch lover right after that. And that was really helpful to me, because I had a rabid butch lover who was really, really affected by me sexually. I mean, I could get whatever I wanted if I just jiggled my ass or my tits or something, and that wore off after a few months, but those three months that our relationship lasted had the most profound impact on me, to have that kind of affect on someone sexually, to use my body in that way, to feel that way about my body. It was just remarkable, it was just transforming. Then after that I got involved in doing S/M, and that just pushed me right over — not only feeling good about myself, but feeling really good about myself, to the point where like, at Folsom I was feeling good, I was half naked, I was looking good, and I had a bad attitude about it. I was like, “Want some? You ask real nice.”

April: I think it’s really interesting to hear that you got the part about using your sexuality as a weapon and a tool, as a toy and a control factor over people after you had an evolved sexuality that was yours. Because that’s all stuff that I picked up when I was really little. That’s what I did to keep myself safe. So, we have the same kind of persona in a way, and a lot of my really powerful, really sexy, really out-there persona is about “I am really powerful and really sexy, and you can’t touch.” It’s from being 13 and 14, and trying to find a way to keep men away from me. I’m glad to see it happens other ways.

Max: I never felt like my sexuality was something to hold over someone, or my fat was something so great that I would have like these coins in my pocket of being fat. “Ha ha, I’m fat.” Wow.

Lea: Eat your heart out.

Dina: It’s really intense. It’s strange too. When l started that relationship I had been working out really regularly, and I didn’t work out for the entire length of the relationship. I was also really busy and there were lots of other reasons, but I didn’t do anything to change what was going on. And I started touching my body more. It created this whole new relationship with my body, to really feel like I was in this body that had the power I always thought of thin bodies as having. This is something you want, and I really want you to beg for it, and drool for it, and really want it, and it has nothing to do with my personality, which was my trump before that … getting sex, getting girlfriends because I was funny or smart or outgoing, and it not having anything to do with my physical beauty, which was really difficult for me at times.

Max: I have no shortage of people who are interested in me, but I always still feel in the back of my mind that it’s despite the fact that I’m fat, not because of it. Despite my body.

April: I feel like it’s only my body.

Max: Wow.

Judy: It’s been very different for me at different ages. I have been unintentionally celibate — no, I was told it wasn’t celibate, abstinent — for 7 years. Prior to that I was very sexually active for a lot of years, although I’ve had periods between relationships that were like a year or two. There was a period when I was intentionally doing heavy-duty non-monogamy, and had 3 or 4 lovers at a time, ongoing relationships for long periods of time, and that was when I was in my late 30s and 40s; that was my peak sexually. I always felt it was in spite of my weight … it was once I was in a relationship that it was different. But I had to be entertaining, funny, intelligent, political, whatever, and then people could get past their stuff about my weight. And I’ve had lovers of all sizes, but mostly fat lovers. I feel safer I think, with other fat women. But not necessarily, I’ve had some really thin lovers who were great. But the thing that’s hard for me to talk about it, it’s very hard for me to figure out what has to do with size, and what has to do with age at this point. Because I’m post-menopausal, and there’s some biochemical stuff that changes. And it’s also very complicated on an emotional level, because I’m also an incest survivor, and I was abused by my father from the time I was an infant. When he died in ’83, I felt like something really changed, and I’ve hardly had any lovers since then. I think that I don’t really know what my sexuality is now. Sort of like that colored how I was sexually to such a degree that I haven’t much opportunity to be sexual. I keep thinking I want to have a lover, it’s like I’m not intentionally not having lovers, but I must be. I couldn’t go for 7 years, given how active I have been. And part of it has to do with age, and not wanting to go through the kinds of struggles that I used to be willing to do. Wanting a more peaceful life. And also disability. I’m real disabled. I’m living on disability. I retired at 54 because I was just too sick to work. So, I can’t separate it all. There’s part of me that wants to be sexual, but there’s also this part of me that doesn’t want to get into close relationships, because my life is really comfortable. I used to be willing to take a lot more risks than I am [now], I’m much more cautious. And I think I have less people being attracted because my weight is higher and my age is higher. And so there’s less options, even if I wanted them.

I don’t really ever meet anybody that’s a possible partner. And for the first time, I’ve really been thinking if I’m gonna get into a relationship I would like a real partner. I’ve never had one, I’ve never lived with a lover. I’ve been out 20 years, I’ve had lots of long-term relationships, and I’ve never lived with a lover. And I’m thinking if I’m gonna do it, that’s what I really want right now. So it’s very complicated. I can’t really separate what part is fat, what part is age, and what part is disability. And how much of it’s coming from me and how much of it has to do with people responding to those different parts. And class! Jew, anti-semitism, yeah.

Jasmine: Well me, I feel like there’s a couple things I want to say in response, but one thing I want to say, for those of you who don’t know, is that I have a daughter who’s 26, she’ll be 26 soon. And it’s just an amazing thing to be in this kind of dialogue with women who are, you’re younger than she is [Dina]. Not that I’m not in intense dialogue with my daughter, too. But she’s not a lesbian, she’s a bisexual woman. And she’s definitely not a fat woman. And she’s very political, and very Jewish, and very out there, and good about a lot of things, but she’s not a dyke. That’s number one. Number two is I know some of you in the room from a distance, some of you better from a long time, and I hear what you’re saying about yourselves and it’s just the perception I have of you. And it feels wonderful to me to know that your perceptions of how you see and talk about yourselves is like how I think of you too. In other words, my vision of the three of you that I know from the community.

Jasmine: My own personal history is that I was disabled as a child, I’ve been disabled since I was very young. I can’t separate disability from fat. I can’t separate it from poverty. I’ve been very poor all of my life. And working class, real working class, you know? And something happened recently, I’m just gonna throw out two things that I think both have to do with fat. Yesterday I went to pick up a friend who was at her therapist’s, who works out of her home in the hills of Berkeley. And I knocked on the door and I had a conversation with this therapist, because the therapy session was running over a long time, and later on when I picked my friend up she said the therapist said I was rude. And what I wasn’t was obsequious, and that’s class. She considered me rude because I wasn’t obsequious. And then I was at another person’s house, and she was talking to me and a friend, and said she didn’t know about disabled people and why were they doing all this work for disabled people? And I do stuff for disabled people, take them shopping and stuff. And she was belligerent, she said, even towards disabled people. She said, “What do they want? They’re always wanting something. They want the bus to wait for them when they get on the bus. Why should they want the bus to wait for them while they get on the bus? Why should we have to sit on the bus and wait for them?” And I got up and I said, “Lady, you are talking about me, and I am outta here,” and I walked away. And before that the two women had been talking about their love lives, and who they were seeking out, and who they were looking for about partners, and it was like I wasn’t in the room. It’s been much of my life. I have never had a partner that’s been a good partner, I have never had a decent sexual relationship for more than two weeks at a time. Not that I haven’t had long-term relationships. I’ve never felt considered as a sexual being, and I know that other fat women are. I know it’s not just about being fat. And I know other disabled women are, and I know other working-class women are, and I know other Jewish women are, and I know other incest survivors are, and I know other mothers are. It’s not any one of those things. It’s all of the way I carry it in my life, and what I think I’m willing to settle for, who I think I’m willing to deal with. So when I hear you talking about how you do what you do with yourself sexually, what your struggles have been, it’s a different picture than … Well, you know, you’re glamorous. You’re April Miller, the glamorous one. And that’s not how you are saying it feels to you.

April: I’m in the middle of writing a piece for the Femme Show that’s just about this. And the thing to me is that I am glamorous, that’s not untrue. That is a real part of who I am, but it’s not all of who I am, and a lot of this enormous presence that glamour has in my life has to do with protection. That’s not something that people see. And I don’t understand why. I think it’s not something people want to see.

Lea: Because then we have to go deep, and have feelings.

April: Damn, I wish I didn’t have to have feelings.

Dina: I feel like I have much more of a presence than I’ve ever had, and it’s always had to do with having something more, in one way or another. I’ve always just skated on the lower level of popularity because I was really funny. I could separate from what kids’ perceptions were of me being a fat kid by really amusing them and entertaining them, and that happens even now. I feel glamorous and I feel beautiful, but it has this level of being over the top, it’s conditioning I learned from drag queens … a way of kind of extending myself a little bit more, and being a little bit more beautiful, a little bit sexier, showing a little bit more cleavage, or having a bigger mouth, or a nastier attitude, or a sharper wit. It’s still that way, the packaging has to be just a little bit more sparkly, and I know that it has specifically to do with size for me. And I don’t always want that. In the beginning I was having lots of fun with it, it was like a new toy. But probably around the middle of summer when I was doing social things like 3 or 4 nights a week, it started to drive me crazy. It became this total persona, it had nothing to do with me, and I was really resentful of it. I was resentful of having to be that person to get this particular response from the dyke community, from the people I was socializing with. Especially from the dyke community in San Francisco, where you can just feel completely invisible. It was like a total cliche, nobody knew me, nobody said a word to me for 8 months, then somebody noticed me, and then everybody wanted my phone number. It was a matter of weeks, and all of a sudden, wow! I was so over it by the time it happened. I didn’t walk into town and tum into the hottest sex toy because I was new in town. That doesn’t have to do with the fact that I wasn’t interesting enough or cute enough. It was because the notice wasn’t there. And it wasn’t there until somebody put it there. And I didn’t put it there. Somebody else had to put it there.

Lea: But that’s societal also, people want what other people have. I mean, have you ever been in a store and you’re looking at something, and before you know it somebody else is looking at it?

Max: Or it’s easier to find a lover when you have one. Or a job.

Lea: I want to say something about what you said Jasmine, and also April and Dina. It’s all related. It’s about the currency of privilege. What is your currency? Is your currency your body? Your class? The color of your skin? It’s very hard, as you say, to break those things down, because I have wondered, walking in the world, as somebody who’s always been a lesbian, and who’s always been visible as one, somebody who’s always been fat except for moments of insanity when I starved, somebody who’s always been working class, and somebody who is a person of color: I don’t care anymore why people feel hostile toward me. It doesn’t matter, but they do. For brief moments in the fat women’s community I’ve had that currency of privilege around my body, and around being butch, and around the fact that I’m good looking. But only in certain circles, and those circles are far and few. So it’s almost like a schizophrenia, and it’s so uncommon that I enjoy it when it happens, even though I’m being objectified, even though politically there’s something that doesn’t work for me in it. But ever since I was a kid I’ve had all of these things about “when they saw me coming.” They saw me coming from a long way away and I think one of the first things they saw about me was that I was fat. I’m a Chicana and I’m brown, but I’m not black. I’m not an African-American person. So the first thing they saw from a distance was a round being, and as I got closer, then the color came into view, then the class came into view … So one of the ways I’ve really compensated, which other women here have talked about tonight, is that I’ve really honed my brilliance. I’m articulate, I’m funny, I have honed those things to compensate. I still feel in the world in most circles, that I really have to prove myself, and yes, after I’ve had a little while with some person, in spite of the fact that I’m fat and those other things, people say “Wow, this person has something.” But it’s crazy-making. If you’re a person of color you have to be 10 times better, if you’re a fat person of color and working class and a dyke, you’d better be a million times better. I just wanted to say that I feel like I straddle multiple worlds, and I’m gonna tell you, I have really had to learn how to do that. I’ve had to learn how to adjust, and how to accept, and how to adapt, you know I’m one of the most fucking adaptable people on the planet, because of all of these goddamn issues! I would like the luxury of not having to be! I have met up with white straight males that do not know how to have discomfort for 5 minutes. I’ve had it for a goddamn lifetime, and it blows my mind. It doesn’t surprise me, but it blows my mind to sit in a room with a person that has so much goddamn privilege that they can’t be uncomfortable for 5 minutes and not lash out at me. What you were saying, Jasmine.

Judy: That’s interesting because I think that answers some of my dilemma that I was talking about, too. I just got tired of doing all that stuff, and since I’m not willing to do it anymore I’m no longer on the market. That as long as I was playing all the games, as long as I was putting myself out there and performing .. .! stopped doing it, and so all my worst fears came true.

April: I’ve been on the peripheries of the Oakland fat lesbian community for years, ever since I moved to the Bay area, and I’m very active in the San Francisco younger fat dyke community. I hear so many stories about women who think I’m “so hot” and “so sexy”, and never even speak to me because I scare the shit out of them. So, there’s something more going on than just that you have to have the sparkle to be in the market. There’s a point where it’s a deterrent or something.

Lea: Don’t you think some people want to be considered enlightened because they find you attractive? I mean, it’s attractive to find you attractive, but they can’t carry it through because of the fat-phobia or the racism, or who the hell knows. We’re talking about fat, and for me, fat — just for me and I don’t speak for anybody else — for me fat has been harder than brown.

Dina: For me fat has been harder than anything. It still is absolutely the hardest thing, and the one place that, well, there’s the story about the guy harassing me on the plane for being fat and reading Fat Girl, it’s the one place where I can feel disempowered so quickly, and that really really bothers me.

Lea: And then there’s degrees. Because this degree [points to Dina] is totally different than this degree [points to Judy]. There’s degrees, and it’s all important, it’s all valid, and some of us have it a lot easier than others.

April: And not that they have it easy, it’s just easier.

Judy: Well, I would say that despite that I have like 6 different things (who’s counting?), fat overall in my life has been the hardest. I mean, it’s the one thing I can’t pass on. At my size, you cannot pass for thin, I don’t care what you do.

Lea: You can’t leave it at home, you bring it with you.

Judy: And I can’t even leave it alone at home when I’m home alone. When I sit in a chair and it’s pushing in my thigh and hurting me. That the world isn’t made for me, that furniture is never comfortable, that I can’t find a place where I really feel comfortable. When I was doing all kinds of political work it was the one I was most resistant to do the work on, because it just seemed so overwhelming. It’d be easier to take a hunk out of sexism, or a hunk out of homophobia, or anti-semitism. Fat just seemed so overwhelming, and of course because nobody was doing anything at that time, there was not support. I would not have done it alone. There was a couple women who dragged me kicking and screaming. They were right. And to this day, after 24 years of fat politics, I still have a hard time with it. I still get most hopeless about everything ever really getting better. I’m not always hopeless, but I have more hopeless moments, I feel more frustrated. It seems like [after) everything we accomplished, then some backlash happens that’s so much worse.

Barb: What about your comfort around dykes whose age isn’t close to yours? Do you feel comfortable? What makes you feel uncomfortable? Also in terms of how you create alliances with fat dykes who are older than you or younger than you?

April: I think I feel most uncomfortable around dykes who are my same age. Partially because I have always known and hung out with people who are older than me, and that gave me a really good basis for when I started to become involved with fat liberation and do reading and stuff. The people who did, like Judy and other people, were older than me, but I could take them as peers in that, and feel like I could be part of the community and move in the community, and like I know what my place is there. I may not always like my place there, but I know what it is, and I’m comfortable. And with people my own age it feels like everything is mine, everything could just fall apart any minute. I guess the currency stuff is harder for me with women my own age. Women who are considerably younger than me, like teenagers, they’re all just still in the enemy category. I know that for me those women are intrinsically untrustworthy, because for me they are still all the people who tortured me in high school.

Jasmine: Me, too. They are the ones. I’m still afraid of them on the streets. I’m still afraid of them, I forget that I’m grown up now. I can’t remember. I walk into a store, and they’re there, and they still frighten me.

Lea: I think part of my experience is about that, even though I had never thought in those terms. For me, ever since I was a kid I was always drawn to older females, always. My friends were always older. And now at this age I have a diverse community, I have women in their 20s, women in their 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, but I’m still very drawn to women who are older than me, for many many reasons I just find a lot in common with them. My last girlfriend was 60 years old and I learned so much. That relationship had such a wealth. The relationship was so rich, and some of that richness for me was because she was older. And I’m ageist. I grew up in an ageist society, and I have to own my ageism. I’m ageist, and I have prejudices about age. And some of them aren’t right, and I know when they’re not right, but I still have them. I talk to myself about them, but I have them, and they’re real. I’m also drawn to children. I love children. And I feel OK in mixed groups. I feel respected by older lesbians, I feel respected by younger ones, too. Not necessarily because of their generosity, but because of how I walk in the world, and what I demand, and that’s one of the things that I demand.

Max: Yeah, I’ve always known older people, too. When I first came out, everybody was way older than me, and everybody was not really completely cognizant of the fact that I was only 15 or 16. Because I looked a little bit older, and I had started college, and so everybody sort of thought I was older than I really was. So, I would sort of pretend I was older. Not like lying and saying I was in my 20s, but just sort of act older than I really was: act like I knew more, act like I’d been through more than I really had, act like I was more self-aware than I really was. I didn’t even really realize I was doing it, but it was just because I was adopting the rhetoric, you know the way dykes are, with all their being conscious about this and conscious about that, and at the time it didn’t mean that much to me, but I tried to be cool and get it faster than I really could. Then there was also this dichotomy going on about a lot of the older dykes, like my lover who was 33, some of her friends hated me before they met me because I was so young and I was dangerous because I was so young, and how could a younger person possibly live up to adult responsibilities in a relationship, and blah blah blah. So there’s always been this sort of push/pull and hate/love thing going on with people who are older than me. Like, “I love you and I need you and you’re my family and my community, and I can’t ever really be like you or be good enough.” It’s weird. And over the past few years is the first time I really have people in my life who are my own age. It’s starting to finally even out a little bit, where I’m less afraid of people my own age, and most of my community is people my own age. And I’m more out of touch with people who are that degree older than me now. And I’ve found with doing Fat Girl, I’m starting to get back into knowing people who are older, and making different assumptions. Like, when we went to the Fat Women’s Gathering we were terrified that people were going to hate us. Because we were being what we thought of as really radical, we had heavy duty S/M in the zine, and we weren’t sure how that was going to be received, because most of the women I had known in my past who were older than me and radically political hated S/M, violently hated S/M. And then here we were, these young whippersnappers coming to the Fat Women’s Gathering. We were pretty close to the youngest women there.

Judy: How did you feel about it?

Max: Great! Great! For the most part I felt fantastic. We were shocked at how well we were received. It was about a million times better than we could’ve possibly dreamed. Because we were scared. We were scared that everybody was going to hate us and that we were going to somehow fail the fat movement, because we were trying to be ourselves, and in a way that we hadn’t seen before. We hadn’t seen these kind of things done by other fat dykes, we hadn’t seen them being radically sexual in print. And so we were scared.

Lea: You get to be who you are, whether I agree with what you do or not, I really respect that you have that place on the planet to be who you are.

Max: That was the feeling I got at the gathering.

April: The experience I have about how people respond to me, both people who are older than me, people my age, and people younger than me, is that they can only deal with one part of me at a time, so they can have respect for me as an articulate, politically aware person at one time, and then they can have some sort of desirous, or envious, or upset, or some sort of sexually based relationship with that part of me at another time, but they can’t do both at once. So the very same people I’m working with, with whom I’m a leader and a struggler and a mover, turn around and discount my presence and the things that I say because I also have sex, or at least they think I have sex.

Max: A lot of people don’t see anything but the sex of the zine.

Judy: I think because it upsets a lot of people. I had to take a long time with it, to tell you the truth. Because my immediate reaction was [grimacing face] like that. I did a lot of co-counseling about it. Because I didn’t have any problem with it except that it was upsetting. Like politically I didn’t have a problem with it, I didn’t have a problem with your doing it. But there’s stuff in there, as a Jew particularly. I have a lot of trouble with some of the paraphernalia of S/M, the leather stuff. And that comes from being raised during the second World War as a Jew. And it feels Nazi to me, and it terrifies me, and it may have nothing to do with Nazi, but the visual triggered me. So I had to work really hard, like I spent a lot of time reading it at different times, and I saw different things as the month happened, I changed about it. But it never occurred to me to think it wasn’t OK for you to do it or that there was something wrong with it or to criticize it. I had to deal with my own feelings about it. And I think that what’s happening is that the younger women are taking the movement another step. You’re pushing the boundaries, and that’s gonna upset some older people. And in order for any movement not to stagnate, the boundaries have to get pushed, and it’s generally gonna be the younger people that are going to do it. And part of the reason you’re able to do it is because we made it possible. We can take some credit, we don’t have to feel threatened by the fact that things are moving on. This is part of being older, that what happens is you do something, and it’s like you did this great thing, and then somebody takes it another step. I don’t want to go there, and so I’m gonna get left behind, and I could get upset about that. I’m not upset about it, but I could get upset about that. Some of us may get upset about where it’s going, but it doesn’t matter. It’s really important that there be room for the boundaries to get pushed, because otherwise we’ll just be a stagnant movement that rots.

Jasmine: It’s tremendously exciting to me to see, because I felt that in fat politics, we stood still. We really stood still. And I was personally, and in community, desperate to know when it was going to change, and what was going to change, and it never occurred to me to go in the direction that the zine has gone at all. It’s just not a page in my book, not something I could turn to. And we as a group would mourn the loss of the respect that we as a group did not have. I mean we have a good community, there is still a good fat women’s community, loosely based, at Swim, at other gatherings … but often in gatherings, whether we’re more than two or three fat women my age or a little bit younger or older, we would very much mourn, “this isn’t changing, nothing’s happening. We’ve worked hard, we’ve written and talked, and written and talked, and performed and nothing is happening. And still the disrespect and hate that a great deal of the lesbian community projects towards us, is quite evident, almost as though none of the work had been done.” And the zine is doing a lot of the work, and April, I think you have done outstanding things too, in being very out there and being glamorous and fun, the two things I personally do understand about the fat movement the whole time I’ve been in it. I didn’t understand that those were the commodities, the coin that you’ve been talking about. Coin. They are coin. Fun and glamour. And that is what the rest of the community will pay with to raise the consciousness. The same things we’ve been saying for 20 years.

Lea: For me, I don’t agree with a lot of the practices that are displayed in the magazine sexually. But you know what? I still benefit from the images. I do. And also from the images that you’ve been so generous [with] April. Every time I see an image of a fat woman and that fat woman is doing good, even though she’s doing things I don’t do, it’s healing for me. And I think the more visibility, the more important, the more advancement we make. So I have to work through my own psychology around those images and everything, but I appreciate them. Just seeing fat women, The SF Weekly, remember the front page? [April was pictured last year.] Oh girl! I mean I tripped! The SF Weekly, these fat women, I mean I get to see you, I swim with you, but everybody in the Bay area’s seeing you. Because it’s something about shame and it’s something about privacy. And it’s something about culture.

Judy: There’s stuff that people don’t get, too. My daughter-in-law was at the Fat Gathering, and she didn’t get it, she thought it was terrible that women were getting up on the stage and taking their clothes off. She’s not a dyke. And what she said was, “What’s the difference between that and the straight meat market?” She didn’t get the difference, and what it means to a fat woman to be feeling good enough about her body to get up in front of a bunch of people and say “I feel good, my body’s beautiful, look at me.” I tried to explain it.

Lea: It’s hard to put into words sometimes, but I just want to say that those images in the SF Weekly prepared me, because I had to work through a lot of stuff. Because I knew everybody was seeing it, I knew a lot of my friends were seeing it, friends of mine that are thin that don’t have fat consciousness that haven’t seen me naked. The work that I did around those images and how I felt about them being public prepared me for Fat Girl and Women En Large. See? I went through a whole process, it was quick, it was healing, it was wonderful, and I still have feelings about it but I can really appreciate in ways that I couldn’t before, because it went public. So there’s got to be political value in that.

April: The centerfold in the first issue of Fat Girl doesn’t work for me, it doesn’t do anything for me sexually, and I think it is the most powerful picture I have ever seen. Because never in my life have I seen a fat girl that big having that much fun in the center of a magazine. If we never put out another issue I have got to say that has got to be one of the most important things we ever did.

Judy: Just because something’s controversial doesn’t mean it’s not a good idea.

Dina: Just last night I was taking my girlfriend out for her birthday and we went to a show, and I wasn’t even thinking of where we were going, and it was mostly straight, mostly straight men, a lot of Led Zeppelin fans, actually. And I went in the dress I wore to go-go dance in, this skin-tight tank dress, halfway up the legs, my tits were hanging out, and a tight sweater, high heels and

stockings, and we were having this sexy date and all that, and about 15 minutes after being in the club I realized, Oh, I look totally, like not just a dyke, but fat with my whole body showing, and for a second I panicked, I was like “get my coat.” But it came and it went like that. Because I was so happy in the moment, happy that the people I put this on for, my girlfriend and myself, were totally happy with it. And then, the interesting other side of it, was that there were straight men leering at me, and I was so removed from the perception that I could be seen like that by the straight world as being another hot, big-titted girl. It was really intense.

Lea: Really watch the evolution of that process, because I’ve been through that, and I can tell you that I used to dress specific ways for specific places. I dress the same goddamn way now everywhere. It’s because of the support, and the healing, and those images. And I’m not self-conscious about it 99% of the time. Something has to happen to make me self-conscious, like threatened, like I’m gonna get queerbashed or something, but after a while it doesn’t even matter.

Dina: It was really profound for me to have that come from within, and after a second of quickly assessing where I was, just walk through that room feeling just as hot as I felt when I walked into that room. Which was pretty hot. It was just really powerful, because when I go to my home town, I gain 20 or 30 or 50 pounds on the plane. I feel really great when I get on the plane, and when I get off I’m not even able to move my body. All the unhealthy stuff that I have from that world just comes back.

Lea: The space they’re holding open for you might be really small. And you’re really psychically preparing, saying “I’m not gonna fit in that space.”

Judy: I wanted to ask if women of different ages feel that women not in their age group are more or less accepting of them as fat women than women in their age group. In other words, do you find that older women are more accepting, or younger women are more accepting?

Max: Yes, older.

April: Yeah.

Dina: Yeah, well … women starting in their late 20s to 30s.

Max: If I think about straight women the story’s a bit different. Like, they never seem to get more accepting, the ones I know, I don’t know that many.

Judy: Well, the straight women in NAAFA.

Max: I don’t know any of them.

April: I feel like it’s sort of an unfair question because the older women that I know are almost entirely fat activists.

Judy: From the time I got involved in the women’s movement, which was about 2 years before I came out, I was always the oldest one everywhere I went. My age group, women were not becoming feminists. I came out, everybody was younger than me, every group I’ve ever belonged to I was the oldest, I’m the oldest one here, and I feel comfortable with women of all different ages, when I’m doing political work particularly, not necessarily out in the world. But I always feel this lack, I feel this longing to have women that are older than me, at least my age. I’ve only had one lover that was my age. When I was 40 I had an 18-year-old lover. It was great, it was a good relationship. But I’ve felt this longing from the time I’ve been a feminist; there are very few women with my politics that are my age or older. There are some, but the percentage is minuscule.

Jasmine: Since I’ve been a lesbian I’ve been an active mother. I’ve been a lesbian over 20 years, and my oldest kid is 25. So I’ve also been older than many women, so a lot of the time women relate to me as mother, and I am very very tired of it, and not knowing how to undo it, and not feeling acceptance from younger women, or women my age, or older women, or women of any kind, but feeling a lot of this “gimme gimme gimme mommy.”

Lea: Well isn’t that also about being fat? We’re perceived like the great earth mothers, the big chichi in the sky?

And at the same time, we’re nurturing, we’re healers. Sometimes it can be a dichotomy. I don’t blame women for wanting that good stuff, but it’s not OK to be exploitative.

Jasmine: But they only want that and they don’t want me as the intellectual that I am, as the powerful leader that I am and can be, as the sexual person that I am. I’m not willing to blame everybody, I’m willing to hold women of the responsibility for it myself, but I don’t know where it starts and ends.

Max: Our society doesn’t value age, our society has this image of sexuality as being only the privilege of this certain kind of person, young, thin, white.

Lea: Childbearing. I don’t want to make babies. That’s not what I’m here for.

Dina: I think that conflict about the mothering thing, that’s really the problem for me. I don’t want to be anyone’s mother. I have had women come to me for that, and that’s not who I am or that’s not what I want there. I have those relationships in my life but from a lover I like to be perceived as what I feel I am and what I feel I put out there. I can be wild and nasty and sexy and I don’t have to take care of you. You can take care of yourself. If you saw me as the person in the same clothes but my body were thin you would look at me differently. You wouldn’t come and put your head on my belly and bury your face in me that way; and come to me in that way. It’s also difficult for me because it was always there for me at a time where I felt I was always too young to be put in that role; like when I was 19 and coming out I had girlfriends who wanted that from me and I was not capable of that.

Lea: I think that wanting the mother is a very important primordial need. I want to honor the mother in me. I’m a good mother, I’m a good husband, I’m a good wife, I’m a good nurse. I can do all of those things. AND I love to mother. But that’s not the only thing I love to do. And that’s not the only thing I’m good at. But I want it appreciated .You’re damn right, I looked for mothering from my girlfriend and the women in my community. I want reciprocity.

Judy: That’s the word!

Lea: I want to honor the Yin and the Yang and I’m good at both.

Judy: But where do you find reciprocity? I don’t know anybody who’s got it.

Lea: Not in one person.

Judy: It is pretty hard to find relationships that are balanced.

Lea: I look to the community for it. I’ll take it in piecemeal cause that’s how I get it. But it’s not about one person. Never. It has never been for me.

Barb: Does anyone have anything in closing that they want to address?

April: I thought that there would be a lot more animosity among the group. I was really pleased to find out that we have so much of the same stuff.

Judy: I wasn’t expecting any. So the younger women were expecting animosity?

Max: I was .. .

April: I was .. .

Dina: I guess I was …

Lea: I was expecting healing and I feel it.

Judy: There was a period of time in the political Lesbian community when it seemed like there were no younger women coming in. It seemed like for long time there were just us old people who had been there from the beginning and there was this gap. And I am sooo thrilled that young women are taking this on as an issue and really moving with it. It really felt like it was going to die with us. And that would have been a real shame.

FaT GiRL 2 Pages

- FaT GiRL #2 Cover

- Comics: Chainsaw

- Fat GiRL #2 is…

- Letters: From the FaT GiRL Mailbox

- Issue Survey – How do you feel the dyke community treats you as a fat dyke?

- Fat Watch

- Stories: Lies I Choose Not to Believe

- FaT GiRL Roundtable #2: Age and Fat

- Poem by Osa Shade

- Actions: Fool the Diet Industry!

- Advice: Ask the Gear Queen

- Recipes from the Kitchen Slut

- 4 Big Girls: Around the Table Review

- Stories: Crossed Paths

- Bend Over!!!

- Poem: i wanna see more ladies flauntin’ it / Photos from MuffDive

- Review: Women En Large: Images of Fat Nudes

- Dinner with April

- The Adventures of Super Slut, #1

- Rant: Is Radical Lesbian Feminism the Only Radical Approach?

- Helpful Hint #9: Enfatten your friends

- More on Apricot Hankies

- Issue Survey: Have you had negative experiences in the dyke community about your body size?

- Selena

- The Fat Truth

- Poetry: The Frigidaire Queen

- Review: The Most Massive Woman Wins

- Review: Fat Girl Dances With Rocks

- Butch Baiting

- Comic: Fat Girl Fantasy #57

- Warning

- Fat Action: A Cunt for a Cunt

- Eat This, Cosmo!

- Issue Survey – Have you had positive experiences in the dyke community about your body size?

- Betty

- Advice: Hey Fat Chick!

- The Adventures of Super Slut, #2

- Resources

- Armchair Shopping

- Fu

- Who are all these babes, anyway?

- FaT GiRL Personals

- Go for a Ride with FaT GiRL

- FaT GiRL #2 Back Cover